To many kids, the word “vaccine” is a sinister one, mostly because it involves a needle. But in the world of medicine, vaccines are considered one of the greatest public health successes achieved. In the 20th century, vaccines have managed to completely eradicate smallpox, nearly eliminate polio, and bring a slew of others under control. In the US for example, measles was declared eradicated in 2000, with a few cases appearing every year as the disease was brought in from other countries.

|

| An infographic showing the influence of common vaccines |

If measles is “eradicated,” though, how come we’re currently experiencing the largest measles outbreak since 2000?

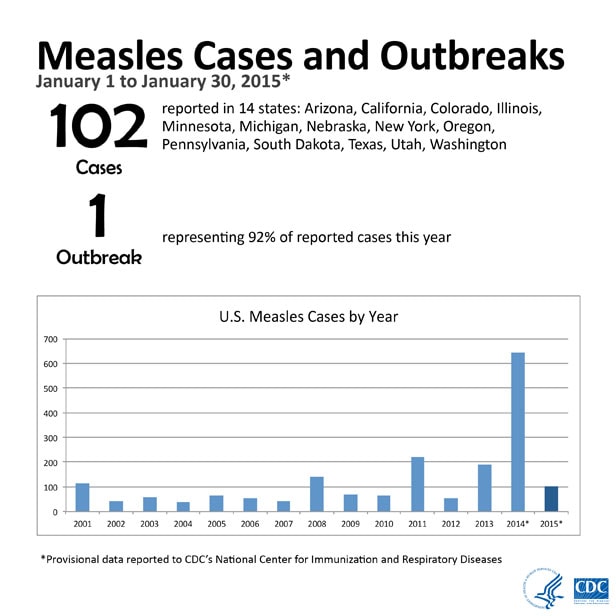

2014 saw 23 outbreaks of measles, totaling more than 600 cases. About 100 more cases were reported in January of 2015 alone, which is significantly more than cases documented in entire years since 2000. The majority of the cases were traced back to Disneyland in California, with one outbreak in an Amish community in Ohio, and were blamed on unvaccinated children contracting measles and subsequently spreading it around at school or daycare once they got home. This is worrying because more and more parents have been declining the CDC's heavy vaccination schedule, especially the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine.

|

| A bar graph from the CDC showing the prevalence of measles since 2000 |

The MMR vaccine is of particular concern, in part because of the negative media attention it has attracted in the past. The MMR vaccine contains a live but weakened virus that can reproduce well enough to alert the immune system, but not enough to cause actual symptoms. After the initial infection, an immune response can be mobilized even quicker in case of another infection. Even though the vaccine virus is mostly harmless, for a long time the vaccine included thimerosal, a preservative that prevents contamination from microbes when the vaccine was still administered in multi-dose vials. Thimerosal was thought to contain trace amounts of mercury, which though harmless in one dose was feared to add up as kids received multiple doses and cause neurological problems. Today the MMR vaccine is administered in single-dose syringes in the US and though thimerosal was shown to be harmless by various studies, it was removed from the MMR vaccine and is used only in two vaccines.

In 1998, British doctor Andrew Wakefield published a study in The Lancet in which he claimed that the MMR vaccine caused autism, prompting many parents to refuse vaccination for their children. Wakefield's results were not reproducible and after an extensive investigation, the doctor had his medical license revoked for publishing a deliberately fraudulent paper. Though the MMR vaccine has been shown not to cause autism, many still associate the two and this negative media attention may be partly responsible for the outbreak we are experiencing today.

|

| A visual of herd immunity at work from The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases |

The anti-vaccine movement would respond simply that having a group of unvaccinated children does not inherently threaten vaccinated children if we believe vaccines are actually effective. But this is where the concept of herd immunity comes in. Basically, the theory of herd immunity holds that the more immunized people exist in a population, the lesser the chance of an outbreak will be. Even if one unimmunized person contracts a disease, it's likely that the chain of transmission will be cut off if the infected person is surrounded by immunized people. Think of stepping stones: unimmunized people are stepping stones the pathogen uses to spread. But if 90% of the population is immunized, the pathogen won't have a stepping stone on which to transmit.

Of course, many still discredit herd immunity, calling it a "myth", and although the theory does represent a scenario of perfect distribution, I would still rather live in a country in which most people choose immunization. Sure, that means we need to accept some risk of rare or manageable adverse effects. We've just come so far in getting so many infectious diseases under control that it would be disgraceful to back down now.

Wow, I really like the graph showing the before and after results of immunization of such diseases as measles. Having grown up in the age of vaccines, I never realized a morbidity rate of half a million people a year simply due to measles! I remember the autism/MMR debate when my children were toddlers and also worrying whether I was doing the right thing by having them vaccinated. I never read any follow ups on Dr Wakefield and how he had been discredited. Great article.

ReplyDelete